ECOSHELTA has long been part of the sustainable building revolution and makes high quality architect designed, environmentally minimal impact, prefabricated, modular buildings, using latest technologies. Our state of the art building system has been used for cabins, houses, studios, eco-tourism accommodation and villages. We make beautiful spaces, the applications are endless, the potential exciting.

2018, Granite State College, Nerusul's review: "Malegra DXT 130 mg. Only $1,04 per pill. Buy cheap Malegra DXT no RX.".

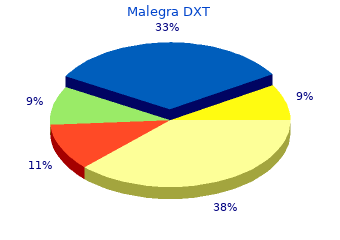

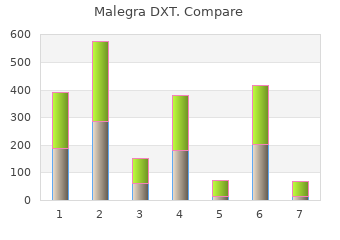

In other words discount 130 mg malegra dxt amex erectile dysfunction young age treatment, concluding that there is a difference or association when in actuality there is not proven malegra dxt 130mg strongest erectile dysfunction pills. There are many ways in which a Type I error can occur in a study, and the reader must be aware of these since the writer will rarely point them out. Often the researcher will spin the results to make them appear more important and sig- nificant than the study actually supports. Manipulation of variables using tech- niques such as data dredging, snooping or mining, one-tailed testing, subgroup analysis, especially if done post hoc, and composite-outcome endpoints may result in the occurrence of this type of error. In other words, the researcher concludes that there is not a differ- ence when in reality there is. An example would be concluding there is no relationship between hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease when there truly is a relationship. By convention the power of a study should be greater than 80% to be considered adequate. As the power of the microscope increases, smaller differences between cells can be detected. This is important Hypothesis testing 113 because a negative result may not be due to the lack of an effect but simply because of low power or the inability to detect the effect. This is fairly common in the liter- ature and includes studies of new drugs against placebo instead of older drugs. Studies of drugs for acute treatment of migraine headaches may be done against drugs that are useful for that indication, but in doses that are inadequate for the management of the pain. The reader must have a working knowledge of the stan- dard therapy and determine if the new intervention is being tried against the best current therapy. Studies of new antibiotics are often done against an older antibi- otic that is no longer used as standard therapy. But, since the current standard is prevention in the form of influenza vaccine, the correct study should in fact have been comparing the new drug against the strategy of prevention with vaccine. This is a much more complex study, but would really answer the question posed about the drugs. Any study of a new treatment should be com- pared to the effect of both currently available standard therapies and prevention programs. Effect size The actual results of the measurements showing a difference between groups are given in the results section of a scientific paper. The effect size, commonly called δ, is the magnitude of the outcome, association, or difference between groups that one observes. It often can be expressed as either an absolute difference or the percentage with the outcome in each group or the event rate. The effect size for outcomes that are dichotomous can be expressed as percentages that achieved the result of interest in each of the groups. When continuous out- comes are evaluated, the mean and standard deviations of two or more groups 114 Essential Evidence-Based Medicine can be compared. A statistical test will then calculate the P value for the difference between the two mean values, and will show the probability that the difference found occurred by chance alone. If the measure is an ordinal number, the median is the measure that should be compared. In that case, special statistical methods can be used to determine the P value for the difference found. The clinically significant effect size is the difference that is estimated to be important in clinical practice. It is statistically easier to detect a large effect like one representing a 90% change than a small effect like one representing a 2% change. Therefore, it should be easier to detect a difference which is likely to be clinically important. However, if the sample size is very large, even a small effect size may be detected. This effect size may not be clinically important even though it is statisticallysignificant.

New insights into the biology of disease are emerging rapidly from a wealth of molecular approaches buy 130 mg malegra dxt free shipping erectile dysfunction protocol video, as well as from new insights into the importance of environmental factors purchase malegra dxt 130mg fast delivery xyzal impotence. However, the system for updating current disease taxonomies, at intervals of many years does not permit the rapid incorporation of new information, thereby contributing to the delayed introduction of advances that have the potential, over time, to guide mainstream practice. The individual-centric nature of an Information Commons is an important means of ensuring that the data underlying the Knowledge Network, and its derived taxonomy, would be constantly updated. Such a dynamic system would not only accept new inputs for established disease parameters, it would also accommodate new types of information generated by newly developed technologies, to identify, acquire, measure, and analyze new biological features of disease. The New Taxonomy Would Require Continuous Validation Bad information is worse than no information. A key feature of a clinically useful taxonomy is the requirement for a validation system. The logic of the classification scheme, and especially its utility for practical applications, needs to be carefully and continuously tested. This is particularly important when patients and clinicians use the New Taxonomy to inform clinical decisions. The New Taxonomy should be routinely tested to provide all stakeholders with data indicating the extent to which decisions guided by it can be made with confidence. Clearly, some patients and clinicians will be more comfortable than others with making decisions that are based on clinical intuition rather than proven evidence. However, a physician should be able to interrogate the Knowledge Network that underlies the New Taxonomy to learn whether others have had to make a similar decision, and, if so, what the consequences were. For example, if a drug has been introduced to target a particular driver mutation in a cancer, a physician needs to know whether or not rigorous clinical testing has determined that the drug is safe and effective. Is the drug effective only in some patients who can be identified in some way, such as by analyzing variants of genes that affect cell growth or drug metabolism? Similarly, if a laboratory test is considered to be a candidate predictor for the later development of disease, has that hypothesis been rigorously validated? Whether a given test is used to identify predictors of disease or the existence of disease, the test result must be interpreted in the context of knowledge about the “normal range” of results. This requirement is not a trivial consideration, especially for tests based on integration of vast amounts of data, such as the genome, transcriptome, and metabolome of the patient. Even with a conventional sequencing test, it is often difficult to ascertain with certainty whether a sequence change is disease-causing or insignificant. Some initial results from whole-human-genome-sequencing data indicate the scale of this problem: most individuals have dozens to hundreds of sequence variants that are readily recognizable, on biochemical grounds, as potentially pathogenic: examples include variants that cause premature-protein truncation or loss of normal stop codons (Ge et al. Toward Precision Medicine: Building a Knowledge Network for Biomedical Research and a New Taxonomy of Disease 48 obscure. Defining and continuously refining our understanding of the normal “reference range” for such tests would require being able to access and effectively analyze biological and other relevant clinical data derived from large and ethnically diverse populations. Ultimately, the Knowledge Network that underlies the New Taxonomy will make it possible to develop decision-support tools that synthesize information and alert health-care providers to all validated insights that emerge from the Knowledge Network and that are relevant to clinical decisions under consideration. The organizational and financial costs of systematically replacing these systems would be substantial. Such issues must be addressed but, given the magnitude of the tasks associated with launching the creation of the Information Commons and the Knowledge Network of Disease, and seeing it through its formative stages, their consideration can safely be postponed for many years. The Proposed Informational Infrastructure Would Have Global Health Impact A Knowledge Network of Disease should ultimately provide global benefits. Inevitably, the Knowledge Network initially would be devised primarily through data acquired, placed in the Information Commons, and analyzed by researchers and medical institutions in developed countries. However, a comprehensive and fully developed Knowledge Network of Disease must include the many diseases, including infectious diseases and disorders linked to geographically limited environmental exposures that are endemic in low- and middle-income settings throughout the world. Therefore, the Knowledge Network effort should be extended to include analysis of data derived in these settings. Improved precision in defining disease is of particular importance in regions of the world with under-developed health-care systems. Disease misdiagnosis in such settings has contributed to the improper use of therapy and the establishment of widespread drug resistance among disease-causing infectious agents. In general, patients presenting with fever in regions where malaria is endemic are administered anti-malarial treatment without direct evidence that the patient actually has malaria.

Increasing physical activity buy 130mg malegra dxt otc for erectile dysfunction which doctor to consult, thereby improving fitness order malegra dxt 130mg on-line erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation underlying causes and available treatments, improves health outcomes of overweight individuals irrespective of changes in relative weight (Blair et al. In addition to the major impact of underreporting on assessment of the adequacy of energy intake, it also has potential implications for other macronutrients. If it is assumed that underreporting of macronutrients occurs in propor- tion to underreporting of energy intake, macronutrients expressed as a percentage of energy would be relatively accurate. Underreporting would, however, overestimate the prevalence of dietary inadequacy for protein, indispensable amino acids, and carbo- hydrate. It could also lead to an overestimate of the percentage of energy derived from carbohydrate. Added Sugars Added sugars are defined as sugars and syrups that are added to foods during processing or preparation. Specifically, added sugars include white sugar, brown sugar, raw sugar, corn syrup, corn-syrup solids, high-fructose corn syrup, malt syrup, maple syrup, pancake syrup, fructose sweetener, anhydrous dextrose, and crystal dextrose. Since added sugars provide only energy when eaten alone and lower nutrient density when added to foods, it is suggested that added sugars in the diet should not exceed 25 percent of total energy intake. Usual intakes above this level place an individual at potential risk of not meeting micronutrient requirements. To assess the sugar intakes of groups requires knowledge of the distri- bution of usual added sugar intake as a percent of energy intake. Once this is determined, the percentage of the population exceeding the maximum suggested level can be evaluated. Dietary, Functional, and Total Fiber Dietary Fiber is defined in this report as nondigestible carbohydrates and lignin that are intrinsic and intact in plants. Instead, it is based on health benefits asso- ciated with consuming foods that are rich in fiber. Fiber consumption can be increased by substituting whole grain or products with added cereal bran for more refined bakery, cereal, pasta, and rice products; by choosing whole fruits instead of fruit juices; by con- suming fruits and vegetables without removing edible membranes or peels; and by eating more legumes, nuts, and seeds. For example, whole wheat bread contains three times as much Dietary Fiber as white bread, and the fiber content of a potato doubles if the peel is consumed. For most diets (those that have not been fortified with Functional Fiber that was isolated and added for health purposes), the contribution of Functional Fiber is minor relative to the naturally occurring Dietary Fiber. Because there is insufficient evidence of deleterious effects of high Dietary Fiber as part of an overall healthy diet, a Tolerable Upper Intake Level has not been established. Thus, when planning diets for individuals, it is necessary to first calculate the individual’s esti- mated energy expenditure, determine 20 and 35 percent of this number in kilocalories, and then divide by 9 kcal/g to get the range of fat intake in grams per day. For example, a person whose energy expenditure was 2,300 kcal/day should aim for an energy intake from fat of 460 to 805 kcal/ day. Likewise, when assessing fat intakes of individuals, the goal is to deter- mine if usual energy intake from total fat is between 20 and 35 percent. As illustrated above, this is a relatively simple calculation assuming both usual fat intake and usual energy intake are known. However, because dietary data are typically based on a small number of days of records or recalls, it may not be possible to state with confidence that a diet is within this range. If planning is for a confined population, a procedure similar to the one described for individuals may be used: determine the necessary energy intake from the planned meals and plan for a fat intake that pro- vides between 20 and 35 percent of this value. If the group is not confined, then planning intakes is more complex and ideally begins with knowledge of the distribution of usual energy intake from fat. Then the distribution can be examined, and feeding and education programs designed to either increase, or more likely, decrease the percent of energy from fat. Assessing the fat intake of a group requires knowledge of the distribution of usual fat intake as a percent of energy intake. Thus, there are several consider- ations when planning and evaluating n-3 and n-6 fatty acid intakes. However, with increasing intakes of either of these three nutrients, there is an increased risk of coronary heart disease. Chapter 11 provides some dietary guidance on ways to reduce the intake of saturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol. For example, when planning diets, it is desirable to replace saturated fat with either monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fats to the greatest extent possible. This implies that requirements and recommended intakes vary among indi- viduals of different sizes, and should be individualized when used for dietary assessment or planning. However, this method requires a number of assump- tions, including that the individual requirement for the nutrient in question has a symmetric distribution.